FAQ

How would a state engage manufacturers to participate in the Netflix model?

A state can issue an RFP for bids on the exclusive rights to a subscription model, in which the state would pay an annual or quarterly payment to the contracted provider over a pre-determined period of time in exchange for access to as much of that company’s HCV drugs as the state needs to treat its residents during that time frame. Bidding manufacturers could also be required to provide screening and patient outreach programs for treatment eligible beneficiaries and patients. The state may also consider including bonus payments or other incentives for reaching specific target numbers of patients treated.

How would a state administer this project?

The way states deliver and pay for healthcare vary widely, which means that the implementation of the Netflix model would probably look different depending on where you go. Some important factors are whether Medicaid is administered directly by the state, or contracted out to health plans. It also depends on who provides treatment to patients. For example, some states already contract with 340B qualifying hospitals to treat prisoners. This also allows them to purchase drugs at a discounted rate for their prison population, a pre-existing arrangement that could be extended to a broader effort by centralizing the purchasing and distribution of HCV treatment through such a hospital. Still other states may have existing programs to screen for HCV and other infectious diseases in their communities, which may offer a means of outreach and care delivery not available in other states.

What patients would the Netflix model include?

The optimal strategy would target all of a state’s residents with HCV, including those receiving state-funded care (Medicaid, prison, state employees), those covered by commercial and union plans, Medicare, the VA, and the uninsured, including at-risk populations. Although this approach would be the most effective way to eliminate the disease statewide, it is likely that budget constraints and logistics/access challenges will require an initial focus on a more targeted population that falls directly under the purview of state government – Medicaid and prisons.

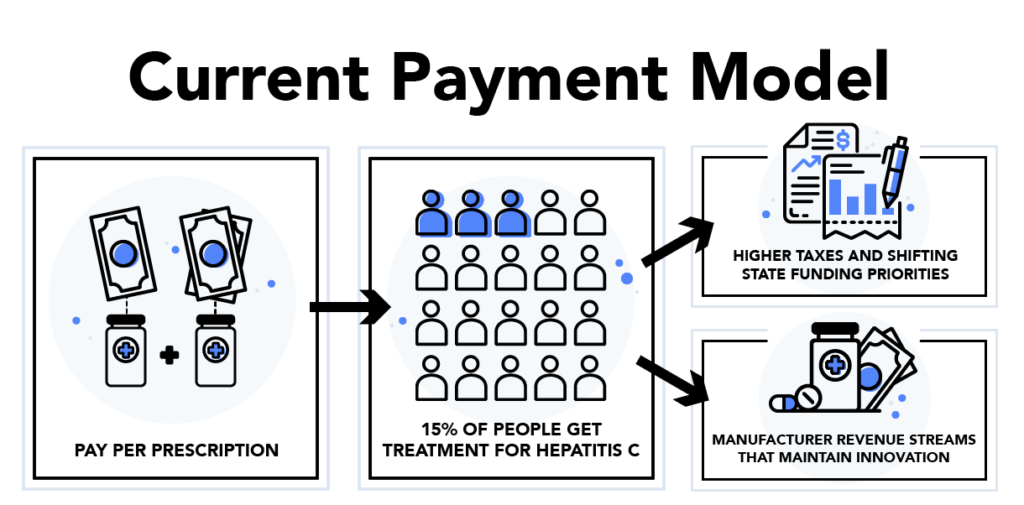

How many patients can realistically be reached with this approach?

Currently, a relatively small percentage of eligible infected patients with either Medicare or commercial coverage seek treatment for their disease. As such, it will be important to consider whether (and how) the state would ensure participation and compliance beyond such level, and what the manufacturers role would be in supporting these efforts.

It is also important to consider that the treatment of HCV, even with the more convenient and tolerable profile of the latest generation products, requires specialized medical supervision and monitoring. Historically, this has restricted treatment to providers focused on hepatology and gastroenterology, and providers in these specialties are not scaled to handle the anticipated volume of patients. To avoid this bottleneck, primary care providers can be trained to diagnose, prescribe, and monitor treatment. (1,2)

Can the state favor one manufacturer’s drugs over another’s?

All Medicaid programs are bound by law to cover the drugs of those manufacturers who commit to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), which ensures that Medicaid programs pay Best Price (e.g., the lowest price in the market for each drug. Although states may avoid this mandate by choosing not to offer pharmacy benefits at all, this is not a practical decision.

In order to explicitly exclude the drugs of the non-winning bidders, the state would have to apply to CMS for a waiver that permits blocking them from their preferred drug list. Alternatively, the state could also avoid the need for a waiver by preferring the winning bidder’s drug, requiring prior authorization for the use of non-preferred drugs, and requiring that patients try the winning bidder’s drug before using another. Either approach would also include an appeals process for patients who for clinical reasons cannot use the winning bidder’s drug.

Doesn’t the Netflix model approach violate Best Price?

Manufacturers are not required to factor Medicaid pricing into their Best Price calculations, so it is unlikely that this would create a problem if the model were applied only to Medicaid. Some states may also draw upon their hospitals with 340B status to act as purchasing entities, similarly allowing them to avoid this route. For commercial populations, however, drug manufacturers are required to report best price to CMS and must report this information at the unit price level. The unlimited nature of the Netflix model would make this unit-level reporting difficult and a waiver or other exception may be needed to allow for reporting that is not unit-based.